“So one day Josef

Mengele goes to take a piss, looks down, and realizes that he is circumsized…”

It was an unusual

setup for my cousin Seymour, lord of cornball humor. Or worse, all those jokes about old people and sex. Or the potty gags he collected and

insisted on sending via email.

When you get a bladder infection, urine trouble. That kind of thing. But he had invited me over to see a

photo that he thought I might be interested in, given my obsession with family

snapshots. So I went and tried to

smile rather than wince my way through his stale routine.

Luckily, a phone call

interrupted his joke and by the time he returned to the living room, he had

forgotten what he was saying, so he took out the photograph and showed it to

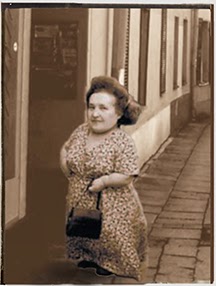

me. Here was a snapshot of a very

very compact woman in a patterned dress that touched the ground. She was standing on the street in Vilna

and holding a handbag. She seemed

to have a knowing smile on her face and a rather proud stance as she stopped to

pose for the camera. Yet she cut

an odd figure in there, so small in the doorway, her head a bit large, her arms

so short. Even so, her whole

demeanor was that of a celebrity, a queen of the ghetto street.

“This is an Ovitz,” Seymour said with

pride. “I don’t know which

one. This photo is one of my

prized possessions.”

“Is she related?”

“No. But she visited Vilna once and my

grandfather took this snapshot with his old Rolex.”

I did not want to

use the word dwarf, which sounded cruel to me, so I struggled for a better one.

“Was she a…um…”

“She was a badchen.”

“Oh, that’s tough.”

“What is?”

“Her condition.”

“A badchen,” Seymour

repeated impatiently but without any insight from me. “Where is your history?

“I left it in

Biology,” I explained.

“A badchen is a

jester, a kind of smart Jewish stand-up comic. They do shtick at weddings.”

“You mean they clown

around, like a court jester?” I asked examining the photo. The idea did not seem to fit her at

all.

“No, that’s a letz.”

“Letz? Our people come from Letz.”

“Don’t remind me,” he

said, doing a Groucho Marx with eyebrows and an air cigar. “A badchen doesn’t do stupid; it’s

verbal humor. Intelligent.”

“Like Woody Allen

before the movies,” I offered.

“Her father was

Shimson Ovitz, a great entertainer from the 19th century. He was my grandfather’s teacher.”

“Your grandfather

was one of these…bad…”

“Yes. You can see where my own heightened

sense of humor comes from.”

Public restrooms, I thought,

but said nothing.

“Shimson Ovitz was

famous but even more so because of his children. They were performers in Europe in the 1930s and 1940s and

she was one of them. Singing,

dancing, playing instruments. They

were called the Lilliput Troupe.”

“Were they all…”

“Dwarves, yes. Most of them. And they were very close. They never separated.

They played together, lived together. This bond almost destroyed them but it eventually saved

their lives.”

This was an

intriguing statement but as he said it, he put the photo down in such a

delicate and melancholy way that I hesitated to ask what he meant. But I did anyway. His answer was something I was not

expecting that afternoon on that scratchy couch in Sunnyside, Queens.

“It was all because

of the man who became fascinated with them.”

I knew where this

was going and took a stab: “An impresario who stole all their money.”

“No. A doctor who was obsessed with

genetics. Dr. Joseph Mengele.”

That name again,

like nails on the blackest blackboard.

I may have lost some history along the way but I knew who he was all

right. Mengele...the Angel of

Death at Auschwitz.

“You see, when the

entire troupe was taken to the camp, Mengele picked them out. He was obsessed with heredity, twins,

anomalies. He thought of himself

as some sort of scientist studying genetics. He was nothing of the sort, of course. But here were special test subjects for

him. He set them all aside in

special living quarters with better food.”

“Why?”

“To study them. To do experiments on them. Hideous experiments. But he also saved them. He kept them alive for this purpose and

they stayed together their whole time there…”

Perhaps Seymour

continued on with this point, or maybe he dropped it then and there. I do not know, cannot remember, did not

hear him in any case. A listener

must learn selective deafness as a form of protection. I learned it then. I did not want Dr. Mengele and his evil

in my head. Not then, not

ever. So when I opened my ears

again, the war was over and the Red Army had liberated the camp.

“You see? They all survived,” he was saying. “All of them. They stayed together, gave each other life and hope. They endured as a family.”

Seymour had lost his

own daughter years before in a boating accident. His wife more recently to cancer. He was alone now and I could hear in his voice that the word

family was difficult for him to say.

It lingered like a single note plunked on a broken piano.

“What is it to

survive?” he asked. “How do we do

it? Must we do something, think a

thing, make a decision to?”

I had no answer of

course, but I knew he was not asking me in any case. God maybe, who never explains. Or the universe, which refuses to reply. Or perhaps only that chilly part

of the brain that knows there are no good answers to the best questions.

“What happened to

them after that?” I asked, trying to move on.

I had to ask this

twice because Seymour’s mood had shifted from light to dark like the waning day

outside and it was dimming his thoughts.

“After the war?” he

finally said. “They toured for a

while, I think, then ran a movie theater.

The point is that they survived and in surviving, they won. Not because they were heroic but

because they lived to tell. They

lived. Perhaps only because they

stuck together. They did not let

go. It is a terrible thing to let

go. There is a lesson there.”

Quickly night

settled like a cloak then, heavy and rough. But I still had one question left. I knew the mood was wrong, but still...

“So what is the

punch line?” I asked.

“The punch line?”

“To the joke.”

“What joke?”

“So one day Josef

Mengele goes to take a piss, looks down, and realizes that he is circumsized…”

I quoted.

Seymour looked at me

through crushingly soft eyes.

“That is the punch line.”

No comments:

Post a Comment